Step 6: Program Delivery

Day 1: Setting the stage

It was important to us to establish a solid foundation of shared expectations on day one of the program. Our first session included an introductory presentation which covered logistics for the week and guided participants through a group norm setting exercise and some icebreakers.

Building community in an online environment

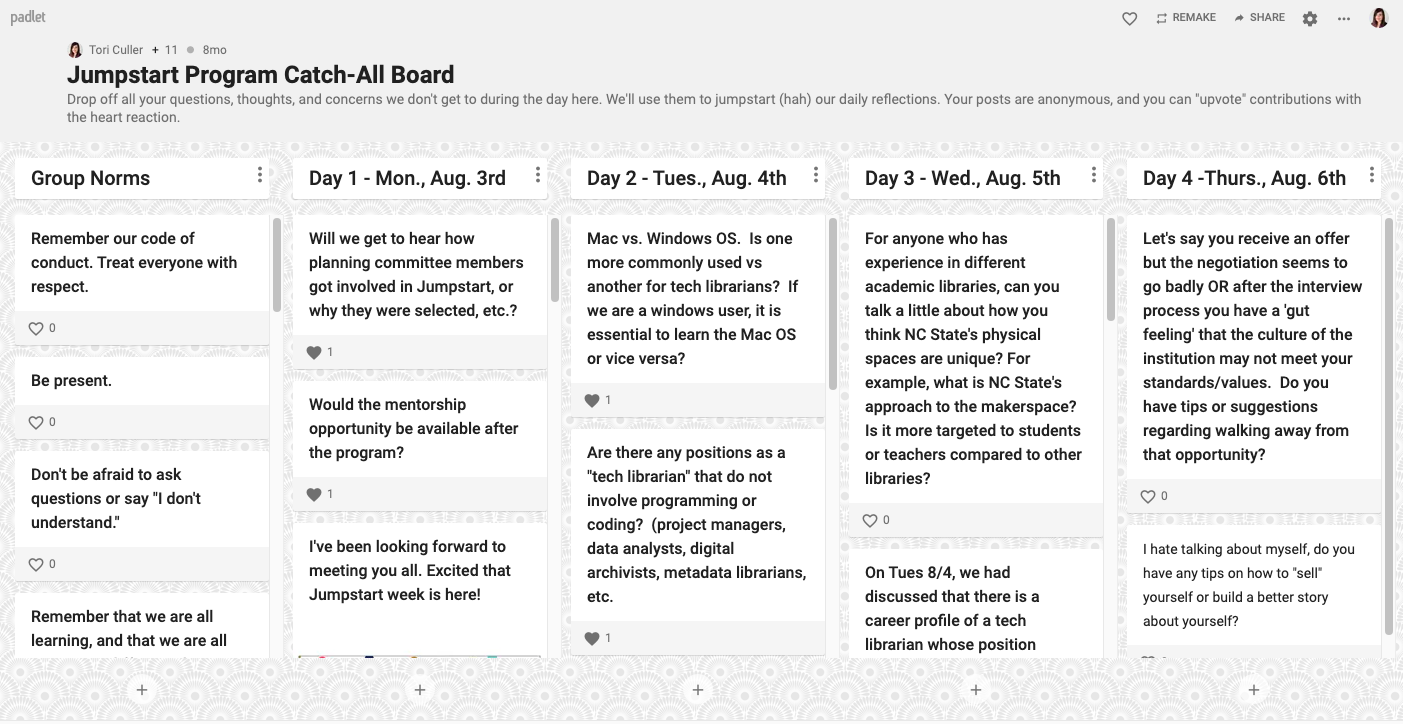

The platform that we used to build our shared group norms on the first day and as a catch-all board for the rest of the week was Padlet. Padlet is a collaborative shared workspace with lots of flexibility that we selected for its ease of use and anonymity.

We used a column structure: the first column held our group norms and participants could anonymously contribute to them at any time. We then created a column dedicated to each day of the program and encouraged participants to add any questions that popped up for them as we went that we may not have gotten around to through the course of the day, or that they may not have wanted to voice out loud for whatever reason. We dedicated the first half hour of each morning to reviewing and answering these questions as a group. We never had a shortage of questions to review and received a lot of positive feedback with regards to this structure.

In addition to the Padlet review at the beginning of each day, we also used gifs and memes as a lighthearted icebreaker by encouraging participants to share appropriate gifs and or memes that encapsulated their current reactions to the program. We found this to be both a fun and meaningful way to engage participants in an online environment as it often led to constructive reflections and feedback.

Facilitating cohort bonding in an online only program is an ongoing challenge. In 2020, we encouraged participants to set up a Slack channel for themselves. We chose not to directly oversee this component as we wanted participants to have a space akin to what they would have had if we had been in person: a place to communicate more informally with one another that didn’t directly involve us as program organizers. While participants did take up the charge of creating their own slack channel, the feedback we received with regards to this is that it wasn’t very active and didn’t quite fill the hole we wanted it to fill. In 2021, then, we opted to forgo the Slack channel and added additional optional social time at the beginning of each day. This optional social time was modestly attended, but seemed to be well received by those who did take advantage of it. In 2022, we brought back the Slack channel and structured it differently: we posted prompts in the forum each day to kick off discussion, created a #participants-only channel, and invited presenters and thers to join the conversation. This seems to been an improvement over our use of Slack in the first year, and continues to serve as a space for participants to connect if they would like. For future iterations, we will continue to brainstorm ways to replicate some of the cohort building elements that participants would receive by default as part of an in person program. We do encourage participants to connect with one another on LinkedIn and to consider reaching out to one anther post-program to engage in continued learning groups together.

Our group padlet was an anonymous space for voicing questions and concerns to help jumpstart daily discussions.

Tip: Take time at the beginning of day one to create shared group norms and expectations. Consider creative icebreakers and social activities to create a sense of community and mutual support amongst participants.

Technical troubleshooting

Technical workshops in-person allow for certain affordances that the online environment does not, including the ability for workshop leaders (or participants) to provide assistance to other participants while the workshop continues. With everyone in the same virtual meeting, there are no side conversations that can facilitate this. Multiple people can’t be helped with different issues at the same time. There’s no easy way to peer over at a neighbor’s screen quickly. For these reasons, it is important to have a plan in place for troubleshooting and asking for help.

The first decision that we made to try to work around the limitations described above is to make use of Zoom breakout rooms for troubleshooting purposes. When a participant needed help, the workshop instructor and helpers would quickly try to solve the problem in the main room, but if it required more focused help, we would send the participant(s) and a workshop helper into a breakout room. We asked workshop instructors to slow down the pace while there were people in breakout rooms so that while the workshop would continue, it wouldn’t be as difficult for participants to catch back up once they were done.

One thing that we considered with the breakout room approach was that if several participants needed help with different problems at the same time, we would need to increase the amount of workshop helpers we had on hand. We ended up asking 3-4 people to act as helpers for each workshop (for 8-10 attendees).

The approach we took to technical troubleshooting worked out well for the most part – we were able to solve issues fairly quickly and the workshops generally flowed smoothly. It did take time for everyone to become comfortable with the transition from main room to breakout room, and when to make that transition. After the first workshop, participants became used to going into the breakout room, sharing their screens, and working through issues. Throughout each workshop, we constantly solicited and incorporated participant feedback to improve the process. In the future, we will try to more specifically document expectations around the process to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Tip: Consider the limitations of technical troubleshooting in a remote environment and create a plan to share with participants, workshop leaders and helpers to establish a process for troubleshooting.

Last updated on September 26, 2022.

From NC State University Libraries. https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/jumpstart